Tariff-ied Yet? A Look at the Global Trade Shakedown

Sara Tariq GandhiAnalyst – Advisory & Consulting

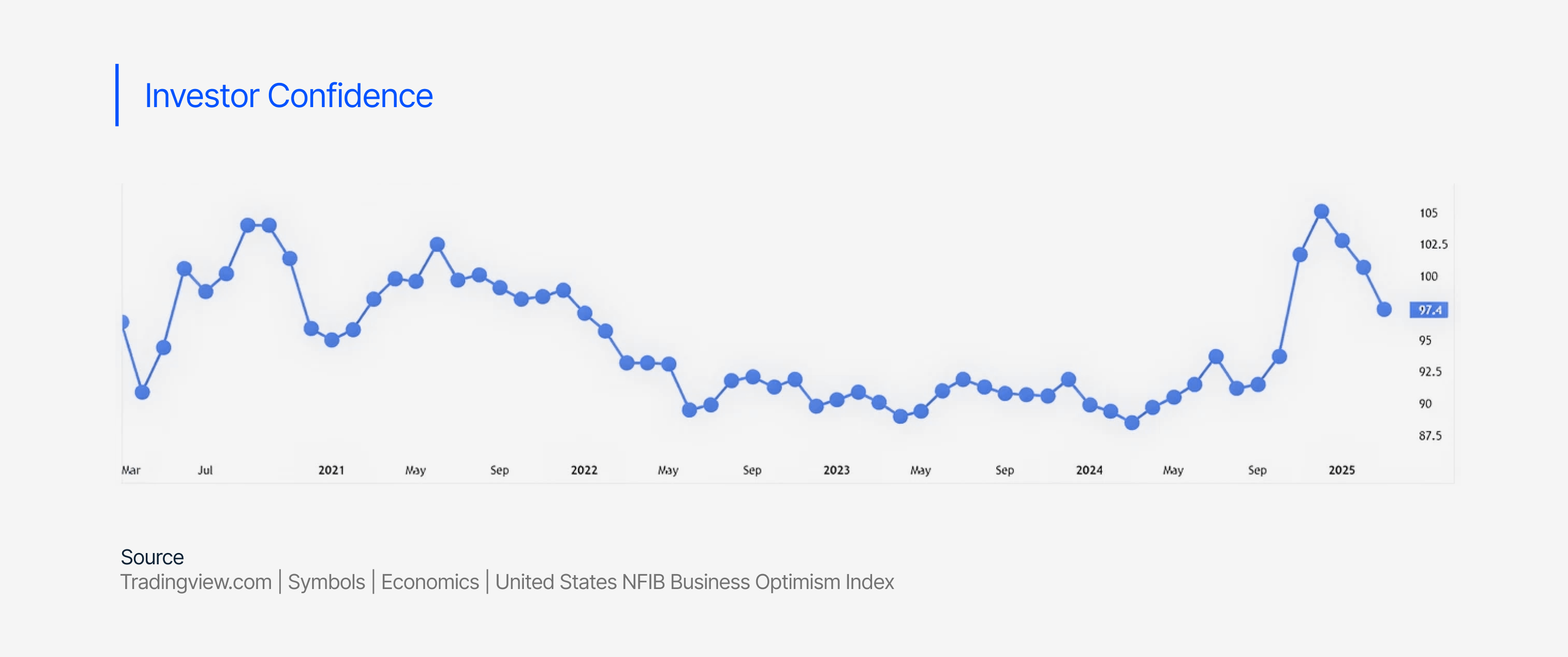

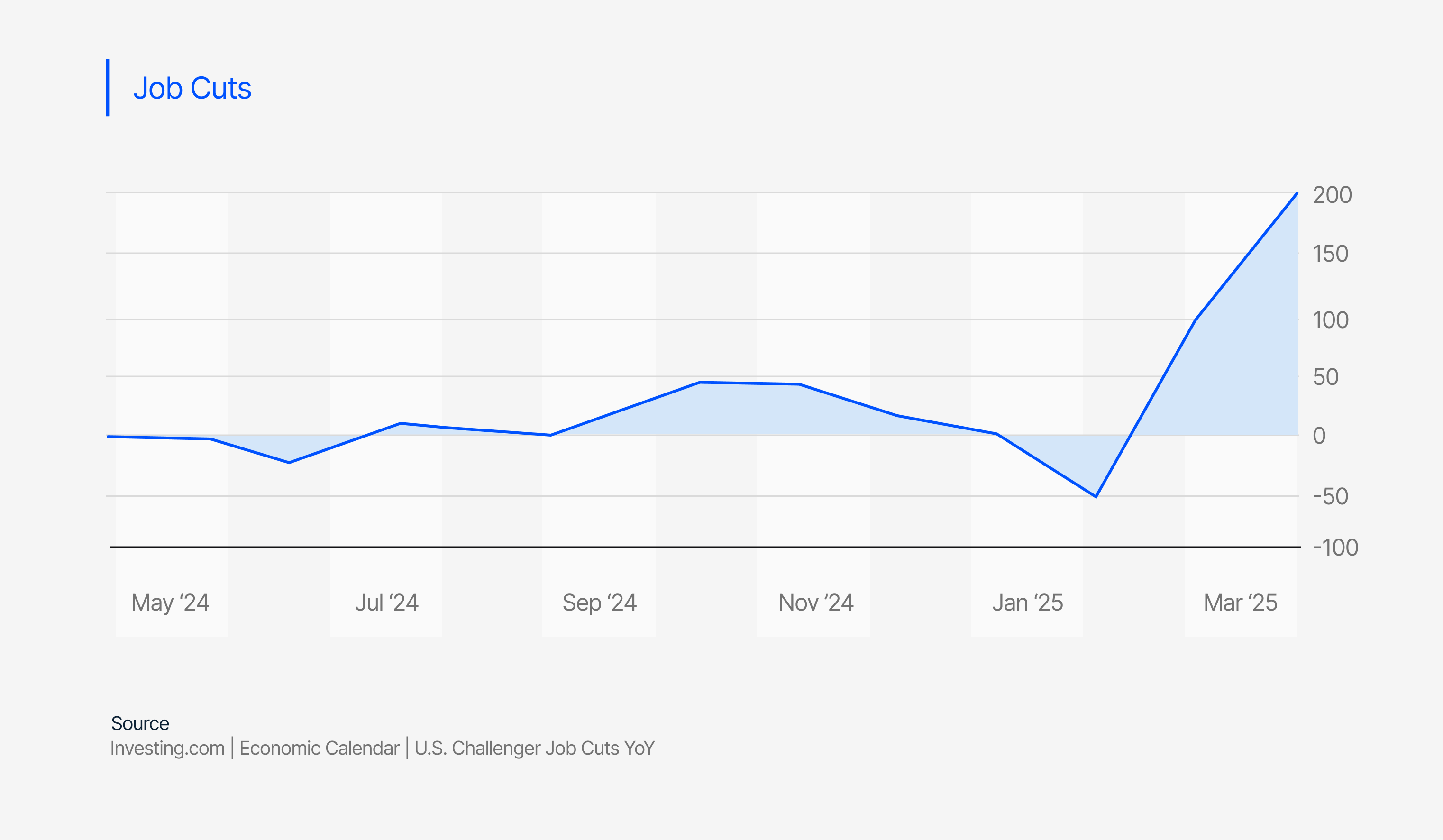

The liberation day tariff regime, characterized by a minimum of 10% and higher reciprocal tariff on 59 countries, has been introduced against a backdrop of pre-existing economic conditions. Notably, prior to these announcements, business optimism was already low, the ISM index indicated a contraction in the manufacturing sector, corporate profit signals suggested a decline in earnings revisions breadth, and there was a significant increase in announced job cuts.

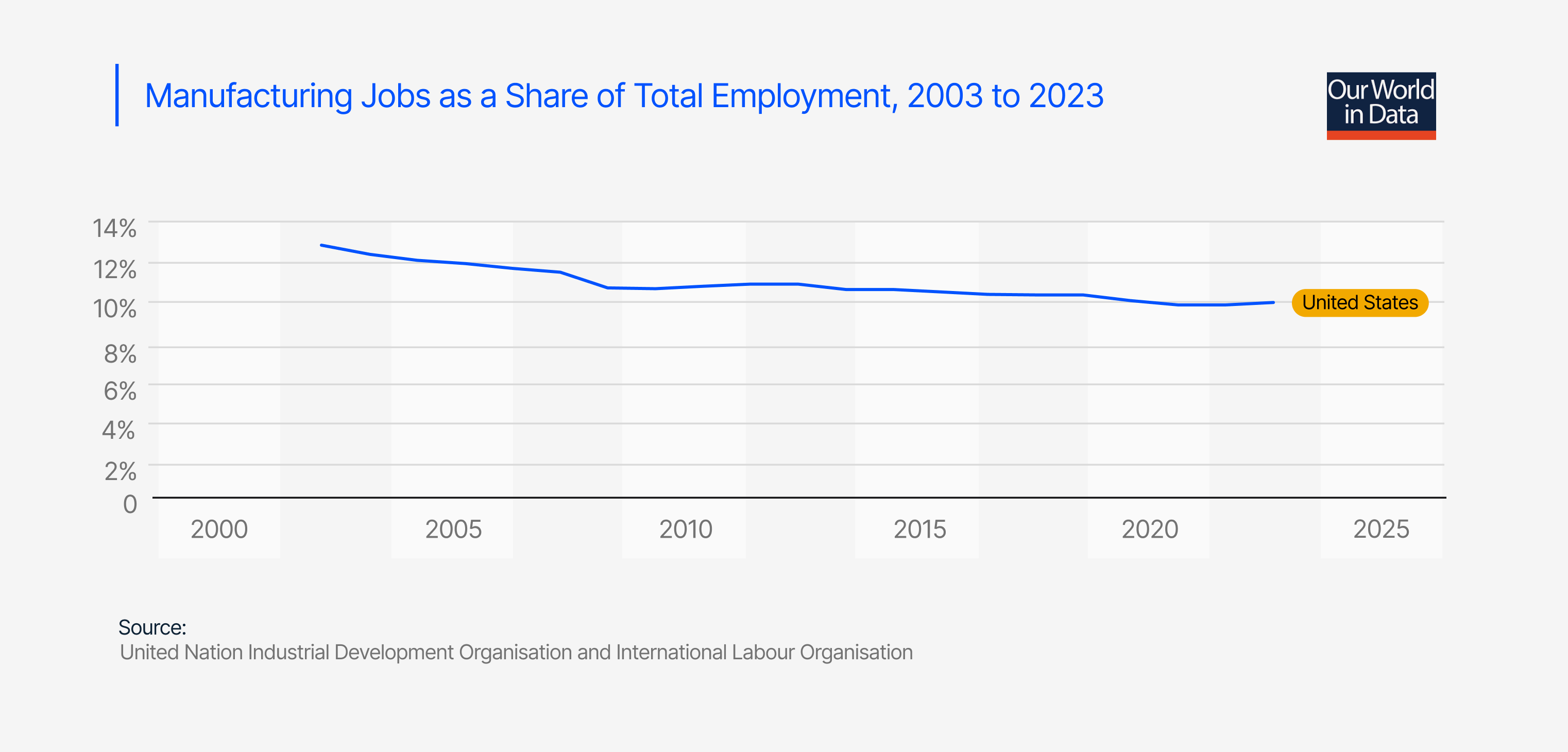

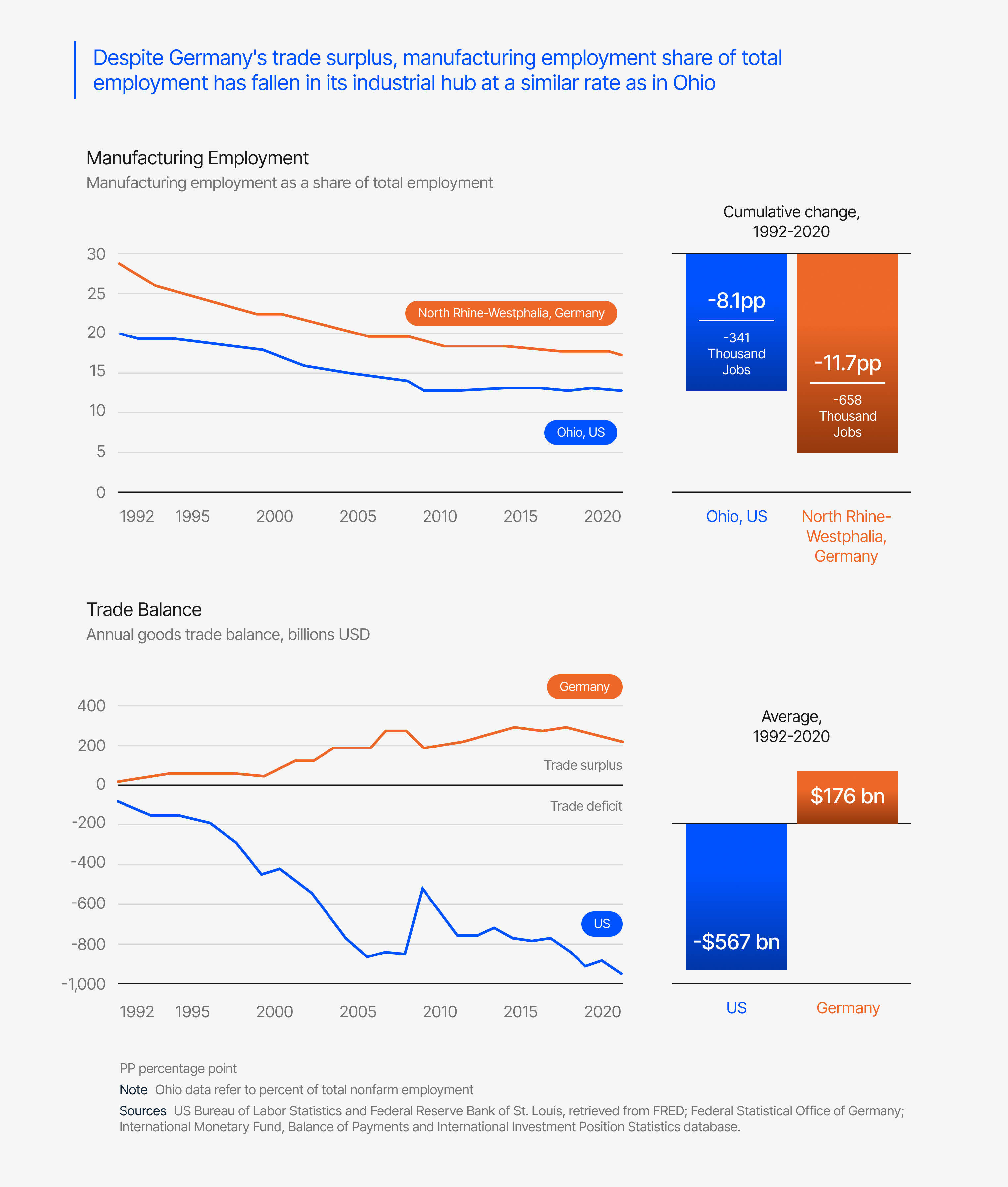

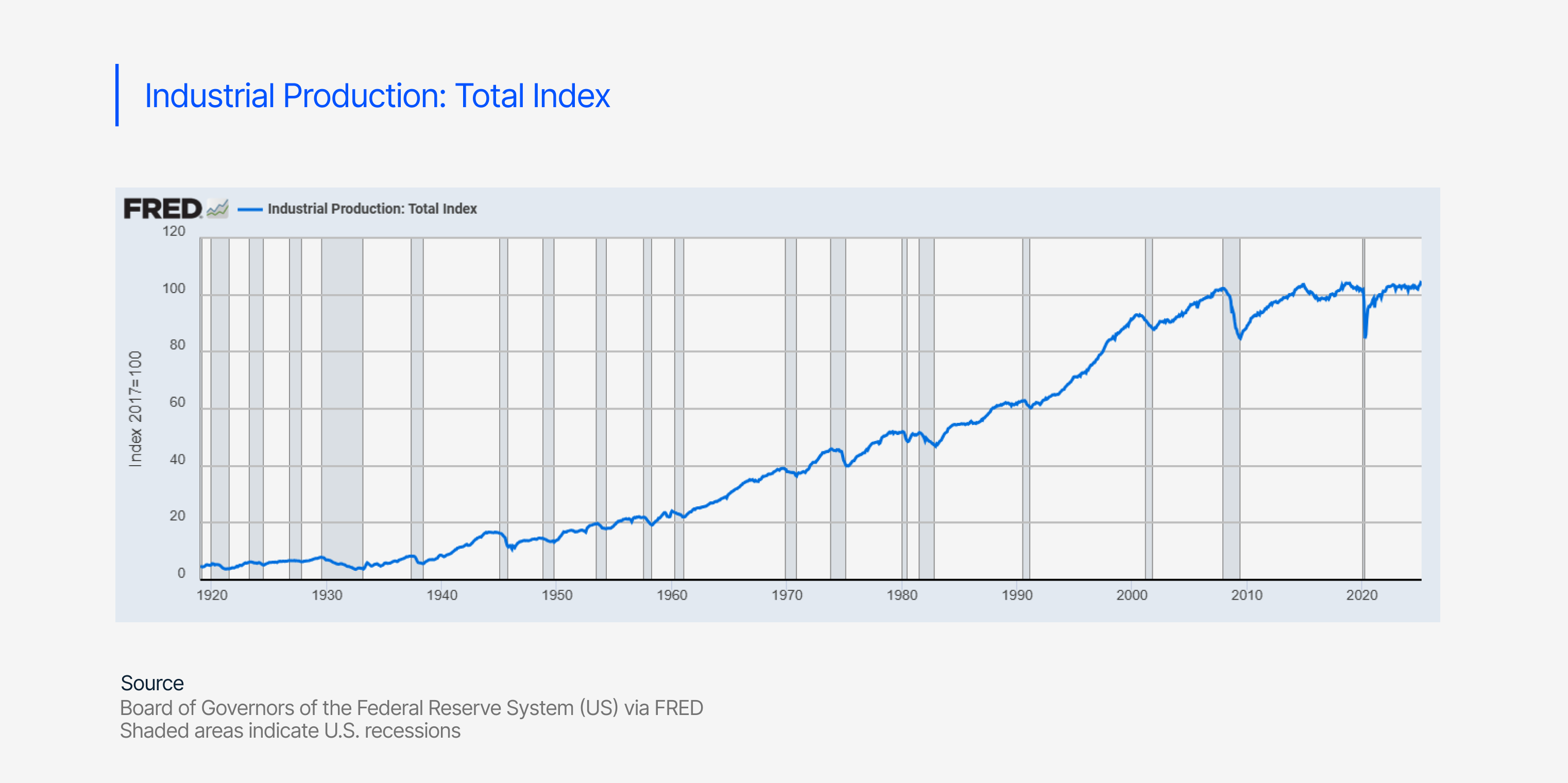

The justification provided by the White House posits these tariffs as a necessary, albeit challenging, adjustment to address persistent US trade deficits, stagnating industrial production, and a decreasing manufacturing share of employment. This perspective highlights the period following China's entry into the WTO, during which US consumer spending and GDP continued to grow while US industrial production declined, suggesting to them a need for intervention beyond distribution and macroeconomic policy. The current administration aims to narrow the US external deficit through fiscal tightening and a tariff-induced decrease in imports, while simultaneously encouraging domestic investment and foreign companies to establish facilities within the US. The ultimate goals include shrinking the domestic savings investment imbalance, achieving more sustainable public finances, and reducing reliance on foreign capital.

However, the approach has elicited considerable skepticism and criticism. One significant point of contention revolves around the econometric formula employed, which considers imports, exports, and price elasticity of tariffs and import demand. A leading economist at Chicago Booth, who authored a paper on elasticity of import prices to tariffs, alluded to the fact that the administration had used incorrect figures in the application of the formula, thereby undermining confidence in the analytical foundation of the tariffs. Furthermore, the absence of tariff rates and non-tariff barriers in the formula is perplexing, especially given that the administration has emphasized these as driving forces behind the need for tariffs. While the bilateral tariff rate differential might seem small, the US itself applies plenty of non-tariff barriers. This suggests a disconnect between the stated rationale and the analytical foundation of the policy.

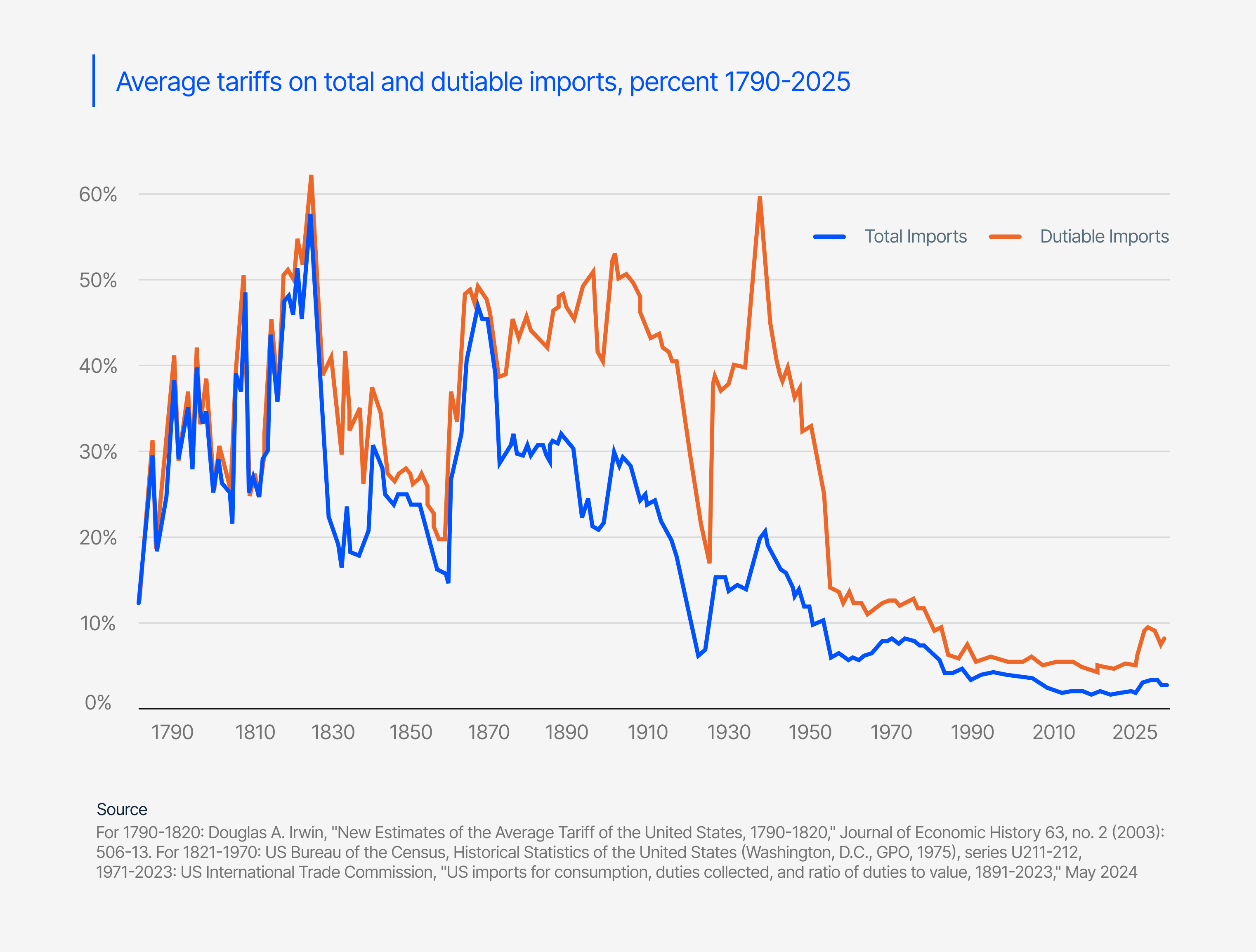

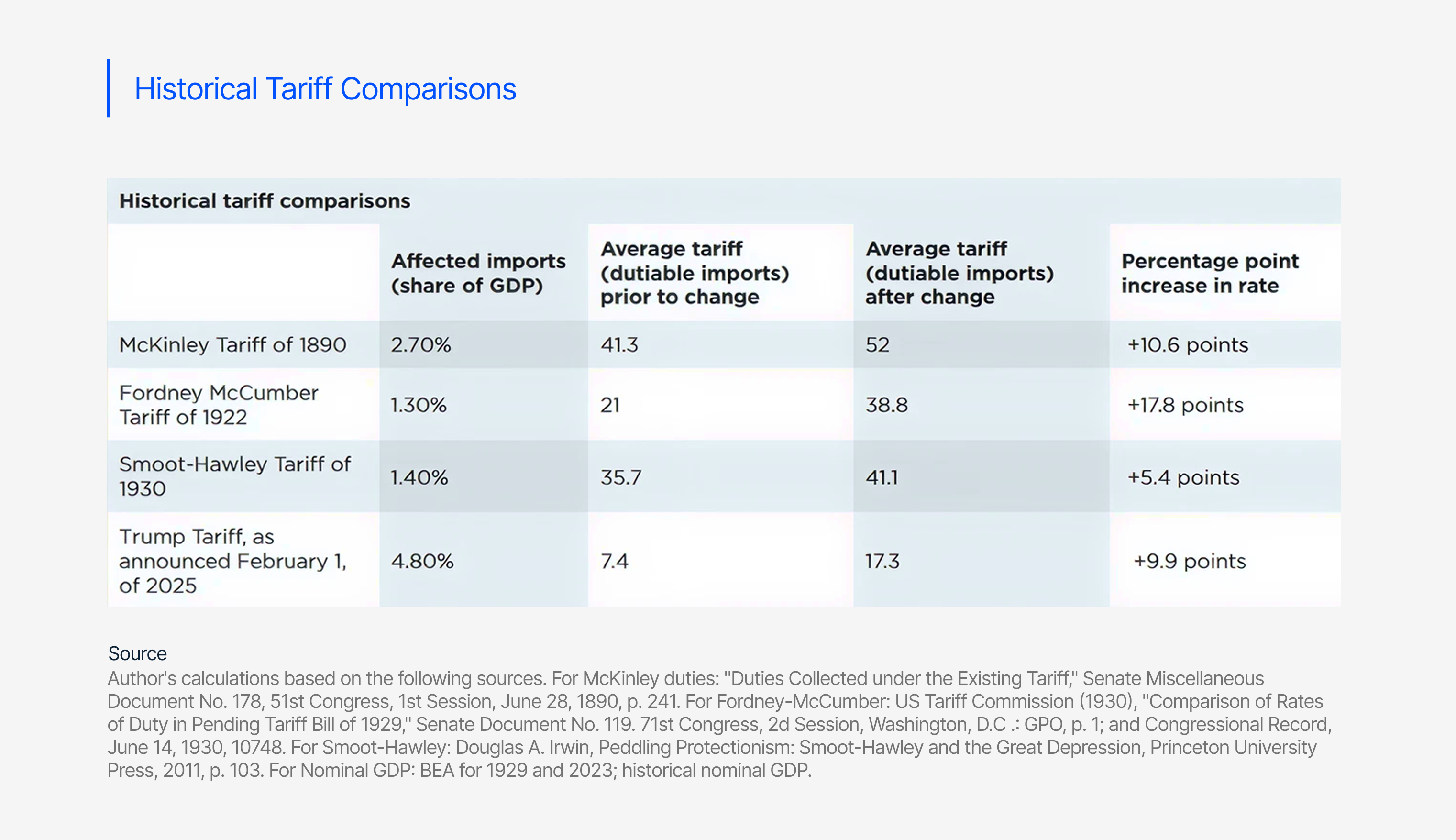

The imposed tariff rates, on average, represent the highest since 1910, and their impact as a share of GDP is the highest since the 1870s. Should these tariffs persist, they would constitute the largest tax hike since 1968 and one of the most substantial in the post-war era, leading many Wall Street economists to predict a 40-70% chance of recession.

Support for the 2025 tariffs has largely been limited to certain venture capital circles, where nostalgia for high-tariff eras like the late 1800s runs deep. But invoking the McKinley period overlooks how different the economic landscape was. Back then, tariffs made up nearly half of federal revenue, but the government itself was a fraction of its current size, and income taxes didn’t exist. Today’s economy is global, government obligations are far greater, and tariffs alone can’t realistically replace broad-based tax systems. Reaching back to a 19th-century playbook ignores the structural realities of a modern superpower economy. Concerns have also been raised regarding the potential for depressive growth amidst a trade war due to the impact of tariffs on inflation, with doubts about growth being sufficient to curb inflation.

While tariffs may be politically appealing and theoretically protective, their practical risks— especially in a U.S. context—are far from negligible. Historically, tariffs have been central to import substitution strategies, where domestic production is favored over imports through a mix of duties, quotas, and incentives. Many Latin American countries experimented with this approach in the mid-20th century, only to find that shielding industries from global competition often bred inefficiency rather than resilience. The U.S. would be wise to heed that lesson.

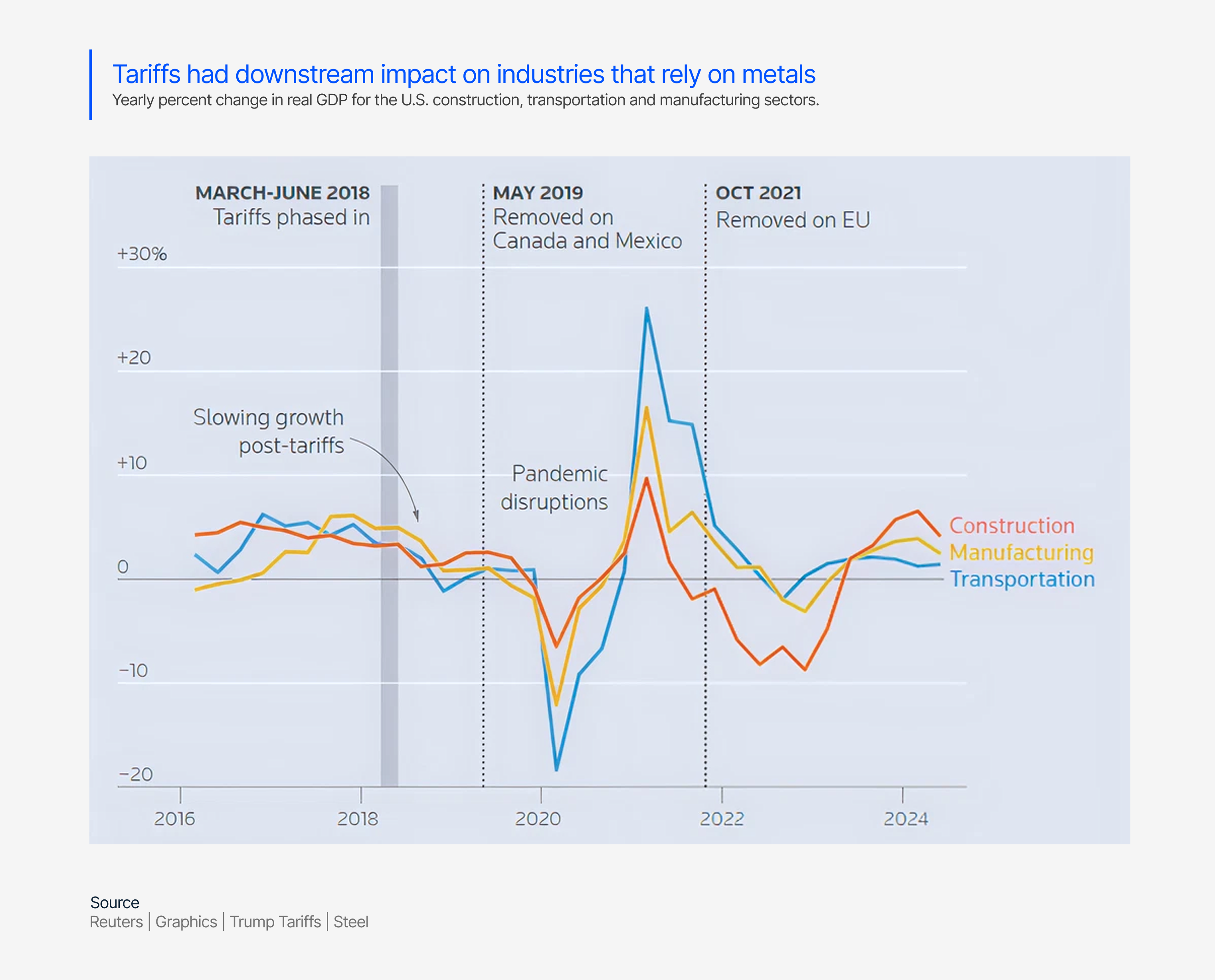

Recent history provides its own cautionary tale. When tariffs were imposed on furniture, appliances, and steel in 2018, domestic production in those sectors didn’t surge—it declined. The logic of revitalizing industry through protectionism failed to materialize, as producers faced rising input costs and disrupted supply chains. Rather than curing industrial decline, tariffs appeared to accelerate it.

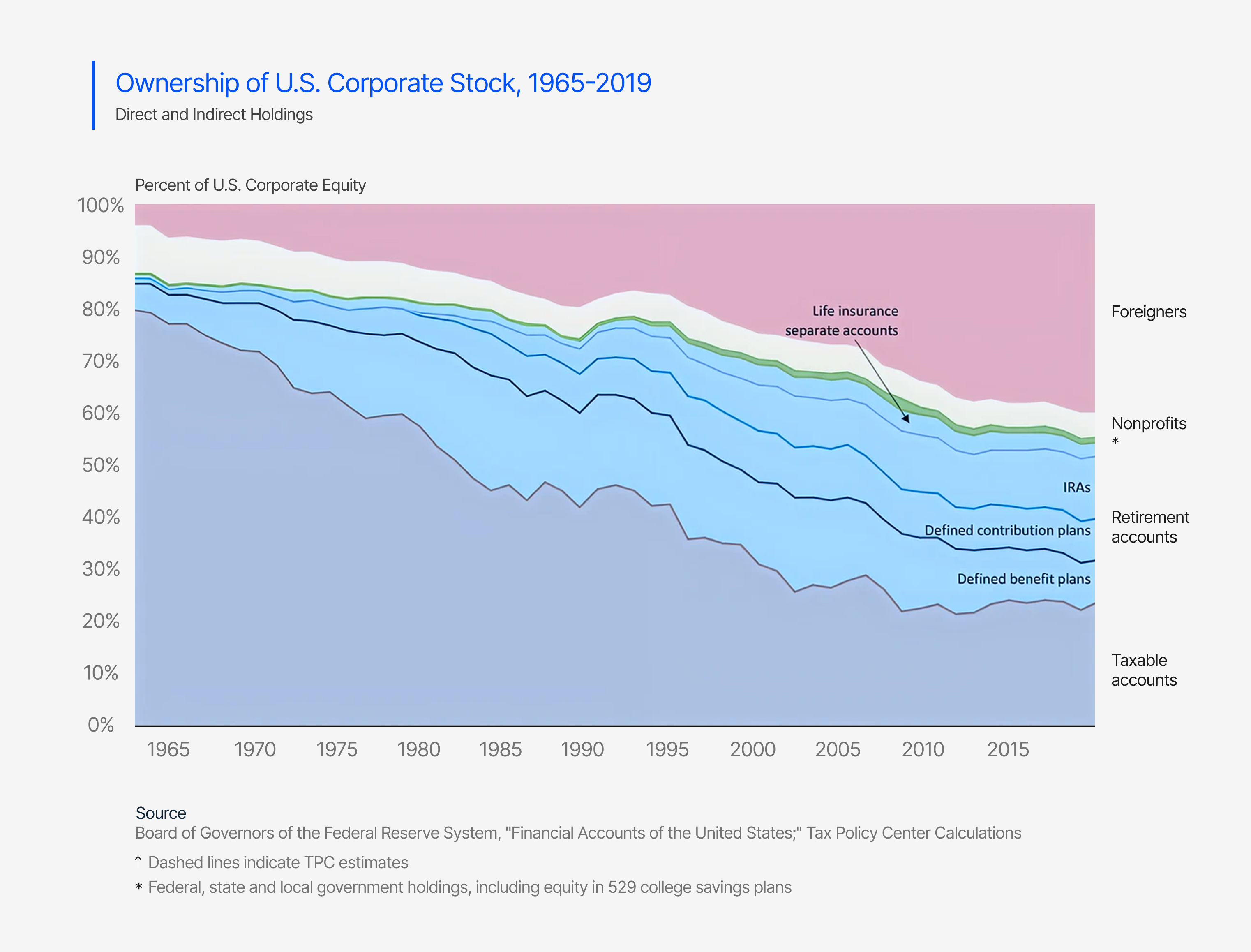

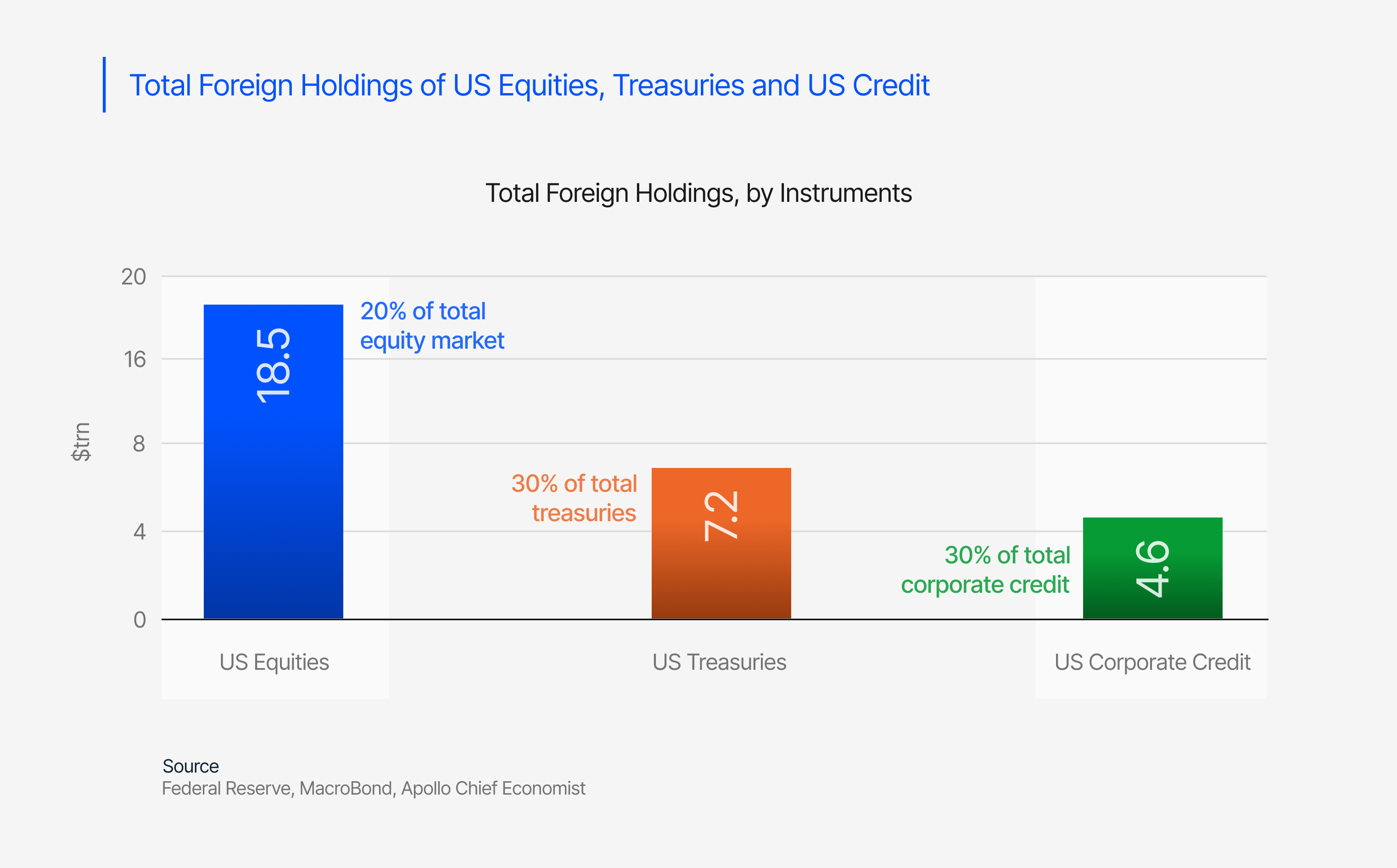

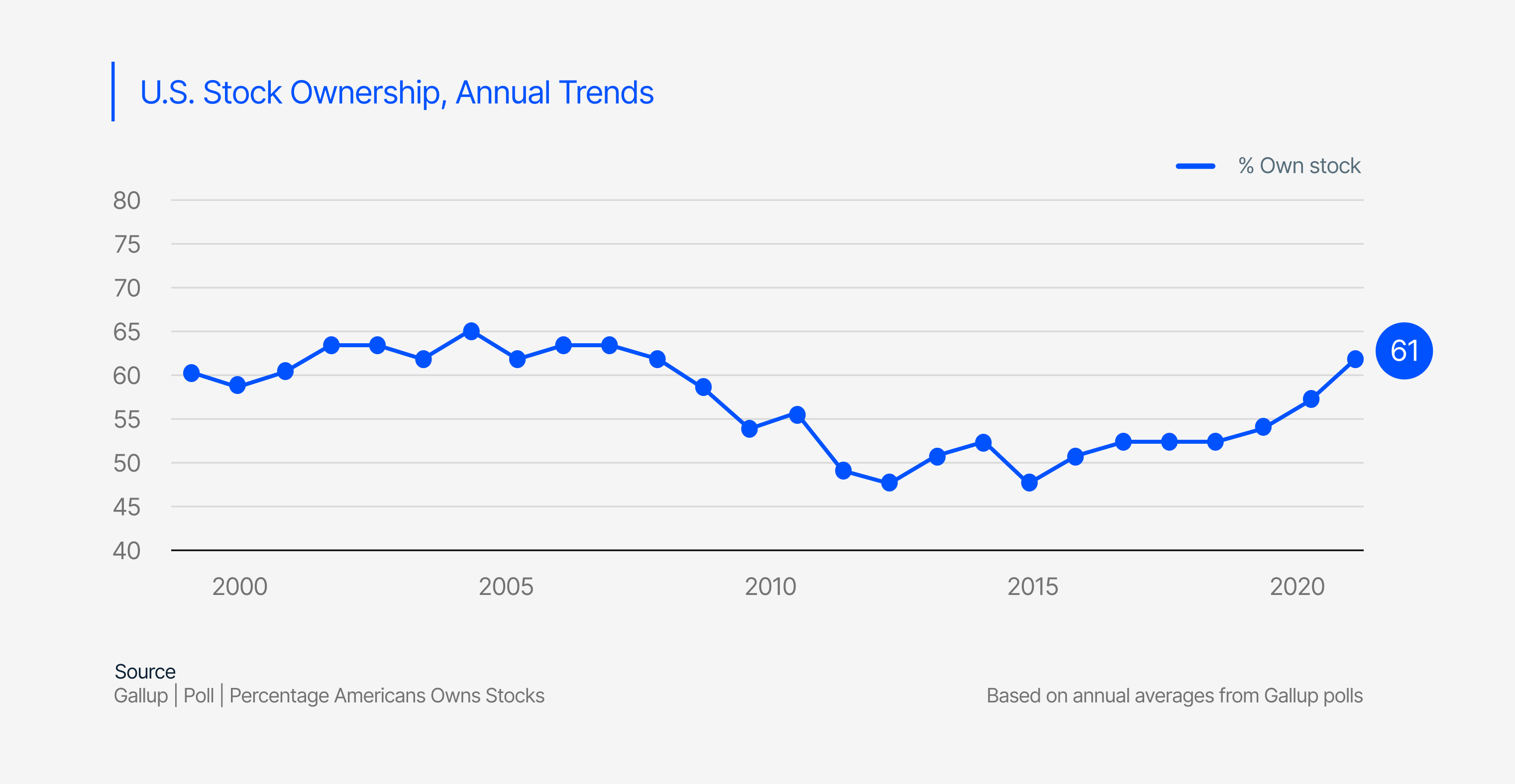

Retaliation from trade partners presents another substantial risk—particularly in the services sector, where the U.S. maintains a strong trade surplus. High-value, digitally enabled sectors like tech and media dominate this space, making them prime targets for countermeasures. In fact, we’ve already seen signs of such retaliation. Should these measures intensify and impact U.S. firms, financial markets may react sharply. The administration has suggested that since 80% of equity wealth is concentrated among the top 10% of earners, stock market fluctuations are of little consequence. But that narrative ignores broader reality: over 62% of American households own stocks, and 42% of household assets are tied to the market. Pension funds—often backed by taxpayers—also have significant exposure. When markets swing, the effects ripple well beyond the wealthy.

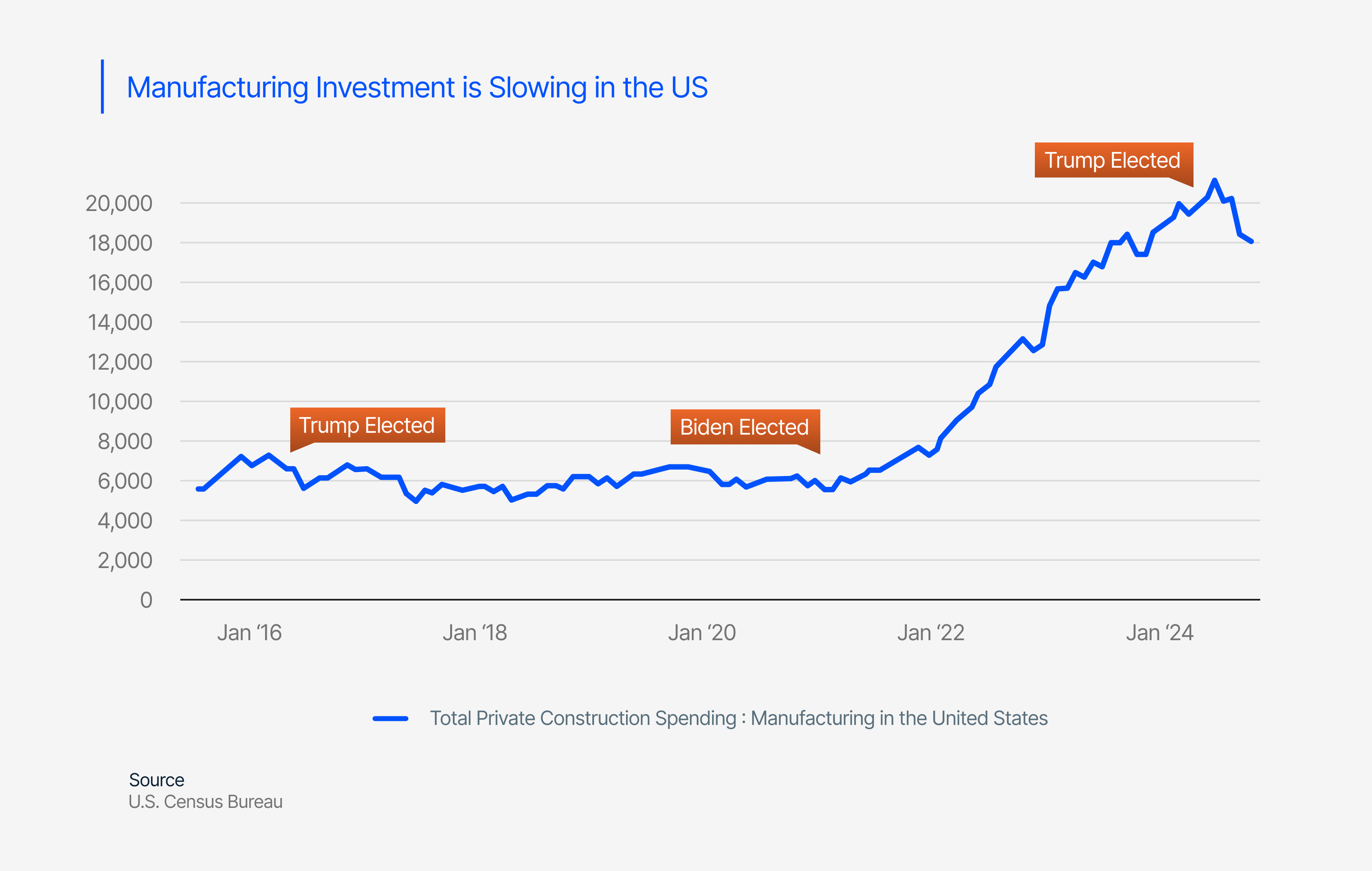

Furthermore, a large share of U.S. imports are not consumer goods but capital and intermediate goods—inputs essential to domestic production. Nearly half of all imports fall into this category. Tariffs on these goods lead to higher production costs and feed directly into producer price inflation. Unsurprisingly, capital equipment spending has already declined, indicating that businesses are pulling back investment in response to uncertainty and rising costs.

There’s also the issue of capital flight. The U.S. stock market has recently outperformed Europe and Japan, but erratic trade policy and the perception of growing economic insularity could reverse that trend. Investors seek stability, and capital tends to flee from environments where unpredictability reigns.

Lastly, the broader goal of attracting foreign direct investment seems increasingly at odds with current policy behavior. While the administration has expressed a desire to bring in more FDI, it simultaneously backtracks on trade agreements, pursues highly personalized legal grievances against corporations and media, tightens domestic labor supply, threatens bipartisan industrial policies like the CHIPS Act, and creates a system where firms must lobby for special treatment. These signals undermine investor confidence and send a confusing message: while the door may be open, the welcome mat is nowhere to be found.

The selective application of these tariffs further complicates the picture. While European and Asian markets are being aggressively targeted, Russia—despite its significant presence in U.S. imports—has been notably exempted. This incongruity prompts questions about the criteria underlying the country selection and raises concerns over the potential for arbitrary or politically motivated enforcement. Many countries have signaled a willingness to negotiate, with the notable exception of China, which has matched US tariffs and taken other retaliatory measures.

Amidst the uncertainty, the sources do point to potential positive market catalysts following any potential sell-off. These include low single-digit tariff deals, a drop in oil energy prices, further Federal Reserve easing, and fiscal easing in Europe and China. Additionally, domestic factors such as bank capital reform, infrastructure permitting reform, and modest incremental stimulus could provide some support.

Conclusion

These new tariff rules represent a substantial global economic regime shift that currently lacks broad support among global investors and economists. The efficacy of this approach in achieving its stated objectives remains highly uncertain, and the potential for significant economic consequences is considerable.

Share With